The Rise, Fall, And Resurgence Of Iowa High School Wrestling

The Rise, Fall, And Resurgence Of Iowa High School Wrestling

Iowa high school wrestling used to be the gold standard but it has fallen on hard times lately. Has this proud wrestling state returned to its former glory?

by Andy Hamilton and Kyle Klingman

To fully comprehend the height of Iowa’s power as a wrestling state, it’s important to look back at three astounding facts and figures.

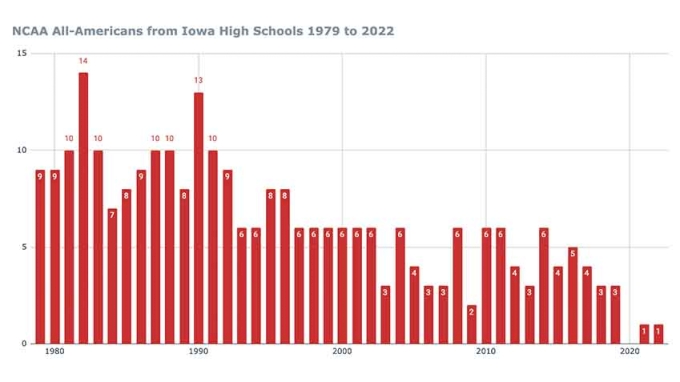

At the 1982 NCAA Championships, 14 Iowa natives reached the podium as Division I All-Americans, including three national finalists from the same public high school.

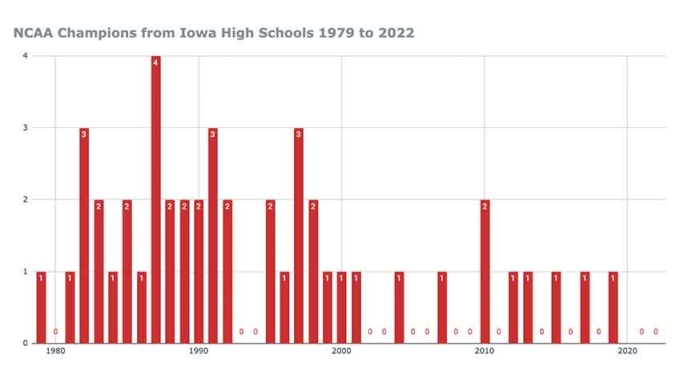

In 1987, four of the 10 Division I national champions were Iowa high school products.

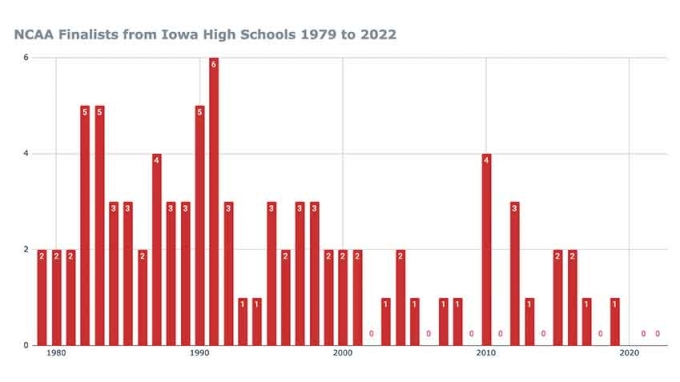

And in 1991, six Iowa former preps — all of whom came from Class 2A high schools — wrestled in the NCAA finals.

For a state that ranked 30th in population at that time, Iowa was unquestionably the national leader in the production of high-level wrestlers. But the rest of the country caught up to Iowa’s technological edge, the Hawkeye State fell behind on the rapidly-changing club scene, the state’s high school travel restrictions limited exposure to top competition, and the state went through a gradual but startling three-decade decline.

In each of the past two years, only one native Iowan — Iowa State's Gannon Gremmel (fifth) in 2021 and Marcus Coleman (seventh) in 2022 — earned Division I All-America honors at the NCAA Championships.

It’s a stark contrast from 40 years ago when one Iowa high school — Cedar Rapids Prairie — had three NCAA finalists and 11 other in-state products earned All-America honors.

“Those are hard numbers to swallow as a coach from this era,” said Iowa USA Wrestling chapter chair Jason Christenson, who stepped down in 2020 as the head coach at Iowa high school power Southeast Polk after leading the Rams to nine state championships.

Iowa’s Rise To National Wrestling Supremacy

Iowans have a love affair with wrestling, but building a tradition took time. One explanation for the state’s rise is that Iowans worked with their hands and that wrestling was a natural outlet for the farming community.

Mike Van Arsdale — a Waterloo native who won an NCAA title for Iowa State in 1988 — says the answer is simple. Large Swedish and German settlements arrived in Iowa during the 1920s and brought fighting systems to a state that had a natural inclination for hand-to-hand combat.

“To add more diversity you had African-Americans moving into Waterloo from Mississippi, Tennessee, and Kentucky,” Van Arsdale said. “These were tough, hard-nosed people who worked in the coal mines or out in the fields. When their kids settled they were from parents who were tough.”

The Boys & Girls Club in Waterloo combined inner-city kids and farm kids that yielded some of the best results in the state at the time. One name from Waterloo would change the course of wrestling history: Dan Gable.

Gable became somewhat of a mythical figure during his unprecedented run through high school and college. He compiled a combined 181-1 record at Waterloo West High School and Iowa State and didn’t lose until his final college match as a Cyclone.

Prior to Gable’s rise, Iowa had produced four Division I NCAA championship teams: Iowa State in 1933 and 1965, Cornell College in 1947, and Iowa State Teachers College (now known as Northern Iowa) in 1950.

Gable’s magical run at Iowa State and his dominant display at the 1972 Olympics in Munich, where he won gold without surrendering a point, became a turning point for the state. Iowans were captivated when one of their own took the world by storm, sparking an explosion in interest across the state that was later fueled when Gable built a college dynasty as the head coach at Iowa.

Many wrestlers, though, point to the 1972 Olympics as a watershed moment since many of the matches were televised.

“I think the rise of Iowa high school wrestling started in the 1970s and 1980s,” said Cedar Rapids native Barry Davis, a three-time NCAA champion for the University of Iowa. “Iowa won its first (NCAA team) title in 1975 and I think things really started to pick up at that time. Iowa State won a few national championships with (head coach Harold Nichols) before that. There’s no doubt about it. I think the 1972 Olympic Games, Iowa State’s success, and Iowa’s success made high school wrestling a mainstay.”

Iowa Public Television was also on the cutting edge of this trend. IPTV broadcasted the high school state finals beginning in 1972 with select college duals beginning in 1977.

That trend continued until 2002 when the state tournament was removed from public television while college duals continued through the end of the decade. Iowa Public Television was a groundbreaking revelation to a state that was on fire for the sport.

It reached all corners of the state and covered a 50-mile radius beyond the borders. It crossed all socioeconomic boundaries since anyone could access the station and, get this: there were no commercials. There was nothing to disrupt the flow of watching wrestling and the action that surrounded it.

“It was the only wrestling on television at the time,” Iowa coach Tom Brands said. “Iowa Public Television was live wrestling and it was the best collegiate wrestling in the country — and it was right in your living room when you only had four stations.”

Northern Iowa coach Doug Schwab of Osage watched his older brothers, Mike and Mark, along with numerous other wrestling stars during the golden era of Iowa wrestling. This was fundamental to his development before becoming an NCAA champion at Iowa in 1999 and an Olympian in 2008.

“I watched Iowa Public Television and I remember thinking, ‘I want to wrestle like that,’ Schwab said. “We took that for granted. We had it and kids got to watch that growing up. Do I think that was an advantage for our kids and our athletes? Absolutely, I think it was. Kids grew up seeing it and wanting to be that.”

Reasons For ‘The Downfall’

Reasons For ‘The Downfall’

Doug Schwab’s final college match came on the big stage at the NCAA Championships in 2001 — a time when wrestling was fighting for television table scraps. At that time, leaders in the sport were willing to move the national finals to a non-traditional afternoon start time just to get the marquee event on national TV.

Twenty-one years later on a hot day in June, Schwab sits inside his SUV in a southeast Iowa parking lot, watching his sons compete at a youth tournament 1,200 miles away in Utah.

“I can punch up anybody in the country and anybody in the world,” he said. “I have access to everything.”

So does everyone else. Iowa’s unique advantage of wrestling on live television has been replaced by streaming services and unprecedented coverage. Prior to the broadcasting boom, coverage of the NCAA Championships was limited to chopped-up snippets that were released weeks after the event. But now, every round of the tournament is shown live.

That’s not lost on Christenson when he ponders Iowa’s place on the scholastic pecking order. There is the reality that the rest of the nation simply caught up when the technological playing field was leveled.

“I think everyone is getting good everywhere,” Christenson said. “These kids today have access to the best technique of anybody in the country, anybody in the world at the click of a button. Kids can step up out of high school and be competitive right out of high school and into college. That learning curve isn’t near as steep as it used to be. The amount of experience and mat time these kids are getting in high school — all over the country — it’s not just in these dynasty states that were for so long, with Iowa being one of them.”

The technological piece is a big part of a larger puzzle, though. Putting the full picture together takes a comprehensive and all-encompassing approach.

Was Iowa on an unsustainable pace and due for a market correction? Did Iowans gain a false sense of security? Were they too slow to evolve?

“What’s the downfall of Iowa high school wrestling?” Davis said. “I think people thought Iowa was so good at the time that we don’t need to train since we’re Iowa. (There was an attitude of) ‘I wrestle for the state of Iowa, so I’m good just because I’m from Iowa.’ It doesn’t matter where you’re from — you still have to train and do things right. You have to change things up. We’re not as dominant as we used to be because of that.”

Bettendorf head coach Dan Knight, an undefeated four-time state champion for Clinton (1984-87) who placed fourth at the NCAA Championships for Iowa State in 1990, has seen Iowa lag behind on some of the sport’s technical and tactical advancements.

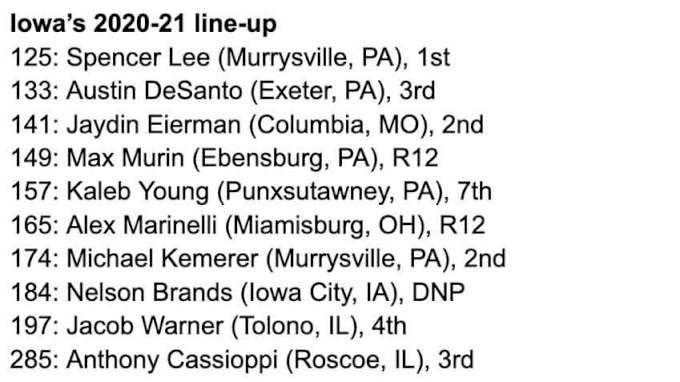

“When all the funk happened, I don’t think we were on the forefront of that,” said Knight, who also coaches at Sebolt Wrestling Academy in Jefferson. “I don’t know if we’re resistant to it, but back in the day we could keep our Iowa kids and you could win with your Iowa kids. Iowa programs had all Iowa kids. I don’t know if you can do that (these days).

“Look at the University of Iowa. They have a lot of Pennsylvania boys on their team and they’re doing pretty well. It’s spread out. The kids are good everywhere.”

One problem for Iowa: The state’s best wrestlers have been limited in their quest to compete alongside some of the nation’s top high school talent. Iowa high school teams are only allowed to compete in contiguous states and Kansas, and those are the only states allowed to wrestle inside Iowa borders during the high school season, according to Iowa High School Athletic Association guidelines.

“If I could pinpoint a couple of things that helped us be successful at Southeast Polk, it’s that our administration and our school board allowed us to go out of state,” Christenson said. “The Cheesehead (in Wisconsin) is the toughest tournament (we could) travel to (under Iowa rules) and we started going there in 2012 and all of a sudden we started winning. I think that has played a huge role.”

So, too, has the explosive growth of club wrestling, which has helped Iowa’s elite gain access to high-level training partners and national competition.

The club scene is flourishing across the country with former college stars lending their expertise. Iowa may have fallen behind this trend but is quickly catching up.

A decade ago, talented young wrestlers were spread out at different locations across Iowa, but they rarely practiced against each other in an organized setting. Top wrestlers facing each other was the foundation of Iowa’s growth during its high school heyday.

“There have been so many people that have tried to start clubs in the state of Iowa,” said Dylan Carew, who owns and operates the North Liberty-based Big Game Wrestling Club, which recently added a site in the Quad Cities.

“It’s easier to answer why it’s different right this second. For me, that’s easy. There are more guys sticking it out. There are three or four clubs that are doing a really good job that have large numbers of good kids. Ten years ago, there were probably too many clubs. When I name the clubs from 10 years ago, I’m not talking about the 15-20 guys who tried to start a club. I’m talking about the guys who made it through that time period.”

Reasons For Optimism

Carew and T.J. Sebolt, architects of Iowa’s two most powerful clubs, sat in the corner in June in Tulsa as several of their top pupils helped the state sweep the Greco-Roman and freestyle titles at the Junior National Duals.

The Greco title — the first in state history — set the stage for a mauling of the freestyle field. Iowa won its eight freestyle duals by an average of 42 points per outing and throttled a strong Ohio squad 47-14 in the championship.

In July, Iowa's Junior freestyle team put on a historic performance in Fargo, running away with the team title with four champions, five finalists and 13 All-Americans. The Iowans racked up 214 points to finish 98 ahead of second-place Pennsylvania. The four champions — Nate Jesuroga, Ryder Block, Aiden Riggins and Bradley Hill — were the most for Iowa since 1983. It was also Iowa's highest All-American count in Junior freestyle since 1978.

The state resurgence has been fueled by scintillating individual performances. Southeast Polk’s Jesuroga claimed a 2021 Cadet World bronze in Budapest. Fort Dodge’s Drake Ayala captured his third Fargo freestyle title in July of 2021. Both Sebolt-trained wrestlers also notched wins at Who’s #1 and won Super 32 belts.

Iowa City West’s Hunter Garvin, who trains under Carew’s watch at Big Game, joined Jesuroga last fall on the Who’s #1 card.

Ben Kueter, an undefeated three-time state champion for Iowa City High who trains with Sebolt, captured a U20 World title.

“Part of what you need, in my opinion, is you need kids that train together,” Carew said. “You don’t need a thousand different little splinter cells. I think we had good clubs 10 years ago. Do I think we had great clubs? Probably not. If you look at us and T.J., you’re talking about two of the best clubs in the United States right now.

“I would put our two clubs in the top seven or eight clubs in the United States, regardless of age. That's unique to have two clubs from one state — especially in a state like Iowa.”

The University of Iowa’s recent recruiting haul is filled with top in-state talent, which is a reflection of a possible resurgence.

“When you rise — unless you just continue to rise — you’re going to fall,” Gable said. “If there’s a good thing about falling is that it wakes people up a little and it makes them a little more focused. It gives them a little more direction. Iowans — when we don’t do well in wrestling, no matter what level, they’re going to perk up their ears.

“When people do well and are known for things that are positive, it labels you and it gives you more notice — and people need more notice. This state needs more notice.”